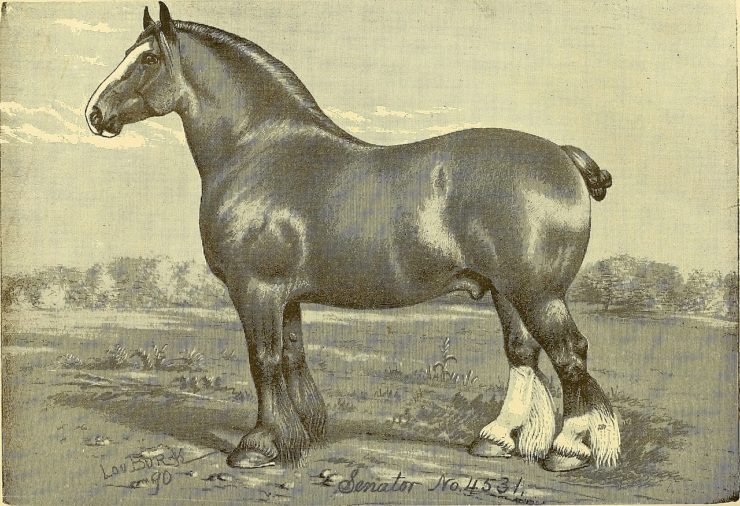

Last time, when I wrote about preserving rare horse breeds, one commenter made an observation about Clydesdales that got me thinking further on the subject. They noted that the modern Clydesdale is quite capable of doing what its ancestors did: pulling a wagon or a plow. The corollary, in other discussions I’ve participated in, is that if the breed as it is now can do what it’s meant to do, isn’t that enough? Do we need to go back to its older incarnation?

This strikes to the heart of the frequent conflict between old and new that runs through just about every breed of horse (and many a breed of dog, cat, sheep, cow, goat, you name it). On one side you have the argument that life is change, and tastes and uses change. If there’s no market for the old type, is that type worth preserving?

The modern Clydesdale is a beautiful animal. It’s the center of a marketing campaign that people truly love. It sells beer, but it also tugs at the heartstrings. When the Budweiser ad department decided to retire the Clydesdale ads, the outcry was loud, long, and strong. And now the big bay horses with the feathers and the chrome are back, telling stories that are both anthropomorphic and, in their way, true to the bond between humans and horses.

That’s a success. The breed, as represented by the Budweiser standard, is both beautiful and functional. Is there any need to go back to the less glossy, less flashy, plainer and less exciting original?

At a Lipizzan breeding-stock evaluation some few years ago, the judge from Austria talked about the wisdom of preserving as broad a range of types and bloodlines as possible, especially in a breed with extremely low numbers—which at that time had the Lipizzan on the critical list (and within the next decade or so, those numbers went down even further). There are breeds and strains that allow and even encourage inbreeding in order to lock in traits that are considered desirable, but it’s a difficult balancing act. The closer the breeding, the more likely it is that undesirable traits will emerge, lethal recessives and killer mutations.

Buy the Book

All the Horses of Iceland

Even if a breed manages to escape that trap, to refrain from breeding animals that carry or produce problem traits, there’s still the question of how far to pursue fashion over tradition. If the current style is a tall, lightly built, refined animal with a long, floating stride, and the breed standard is a short, stocky, sturdy horse with high knee action and more of a boing than a float, how far can or should a breeder go to cater to fashion over standard? Should the standard change with the times, or should breeders try to hold the line? Why should they hold it?

The judge at the evaluation observed that people are taller now, so taller horses make sense. But he also noted that the taller the horse, the less proficient they tend to be in the gaits and movements that distinguish the breed. “They get too tall, they lose piaffe and the Airs.” The short, stocky build and the short, solid legs create the physical strength that allows the peak of performance, and keeps the horse sound for decades, rather than breaking down halfway through the teens.

One solution he recommended was to maintain a range of sizes and types. Breed for slightly more height, but be sure to preserve a root stock of smaller, stockier animals. The mare he loved best at that evaluation was on the short side of the standard, but deep in the chest and hip, powerful in the back, and extremely scopey and elevated in her movement. She defined, for him, the true old type, the horse of the Renaissance. From her one could breed a taller, more modern type, and she would also match well with a taller, more refined stallion, in hopes of producing an ideal combination of both.

A breed exists for specific reasons. It has a distinct look and personality and way of going. You should be able to look at a Quarter Horse or a Morgan or a Thoroughbred or an Arabian, and know that that’s what you’re seeing. Some subsets of these breeds may tend toward extremes—the massive bodies and complete lack of leg angulation in halter Quarter Horses, the extreme dished faces and ultra-refined throats of halter Arabians—but the general population will still show variations on these themes. Stocky, compact Quarter Horses with their long, sloping hips; light, elegant Arabians with their convex profiles and high-set tails.

These traits have a purpose. The Quarter Horse is a sprint racer and a stock horse, built for quick bursts of speed and rapid changes of direction as it herds cattle and rides the range. The Arabian is a desert adaptation, tough and heat-tolerant, bred to run for long distances over harsh terrain.

Both of these breeds are numerous and versatile and justly popular. Smaller breeds, heritage breeds, have their own histories and traditions, and their own sets of standards. Many developed in particular regions, for particular reasons. The Clydesdale was bred for farm work, for pulling a plow or wagon. The Lipizzan was the mount of generals and kings, bred to perform high-school movements that had some use in war but became an art in themselves. Others, such as the critically endangered Hackney horse, is a fancy, high-stepping carriage horse, much in vogue before the domination of the automobile, and now almost extinct.

Sometimes it’s almost a fluke that a breed survives. The Friesian was all but unheard of before Ladyhawke introduced the beautiful Goliath as its equine star. Fans of the film became fans of the horse, and the breed that had been best known for pulling funeral coaches became one of the “romantic” breeds, starring in many a costume drama, and even developing somewhat of a following in dressage.

Preservation breeding is a labor of love, but it’s also a gift to the species. It preserves genetics that might otherwise vanish, and it expands the range of types and traits and functions that, in the aggregate, define what a horse is. I wish people had known about it, way back in the beginning, before the original wild strains were lost, and breeders concentrated on certain bloodlines and allowed all the rest to disappear. Who knows what we’ve lost, or what we might have had, and what we could have learned from it.

At least now we have some understanding of why diversity is desirable, and groups of breeders and enthusiasts who want to preserve the rarer types and lines. There’s ample room for changes in look and type and style, but it’s worth it to keep the old type, too, both as a historical artifact and as a base to build on. Fashions change, after all; sometimes they move forward in completely new directions, and other times they go happily retro. Then the old type becomes new again, and a new generation learns to appreciate what it has to offer.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks. She’s written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.